“Yet Pompeii, today more than ever, has need of its Antiquarium. The gradual expansion of the excavations, the preciousness and uniqueness of certain discoveries, the duty, the inescapable duty, to defend all that cannot be kept outside from atmospheric agents and dangers, if not from the ill-will of men, and finally the usefulness of presenting materials grouped together and categorised, which are not to be found in the houses …”

Amedeo Maiuri, 1967

The Antiquarium of Pompeii was built by Giuseppe Fiorelli between 1873 and 1874 in the area below the terrace of the Temple of Venus, overlooking Porta Marina. It was the exhibition venue for a selection of finds originating from Pompeii which were representative of the daily life of the ancient city, as well as for casts of the victims of the eruption.

In 1926, it was expanded by Amedeo Maiuri, who as well as adding large maps indicating the updated developments of the excavations since 1748, and enhancing the collection with new finds from the Villa Pisanella of Boscoreale as well as more recent excavations of Via dell’Abbondanza, laid out a route which guided the visitor through the history of Pompeii from its origins until the eruption.

The building was seriously damaged by bombing during the Second World War in September 1943, but thanks to the restoration works under Maiuri, on the 13th June 1948 it reopened to visitors as part of the celebrations of the second centenary of the excavations of Pompeii. Damaged again, this time by the 1980 earthquake, it closed to the public.

In 2016, after thirty six years, it was reopened to the public in the new guise of a visitor centre and museum venue.

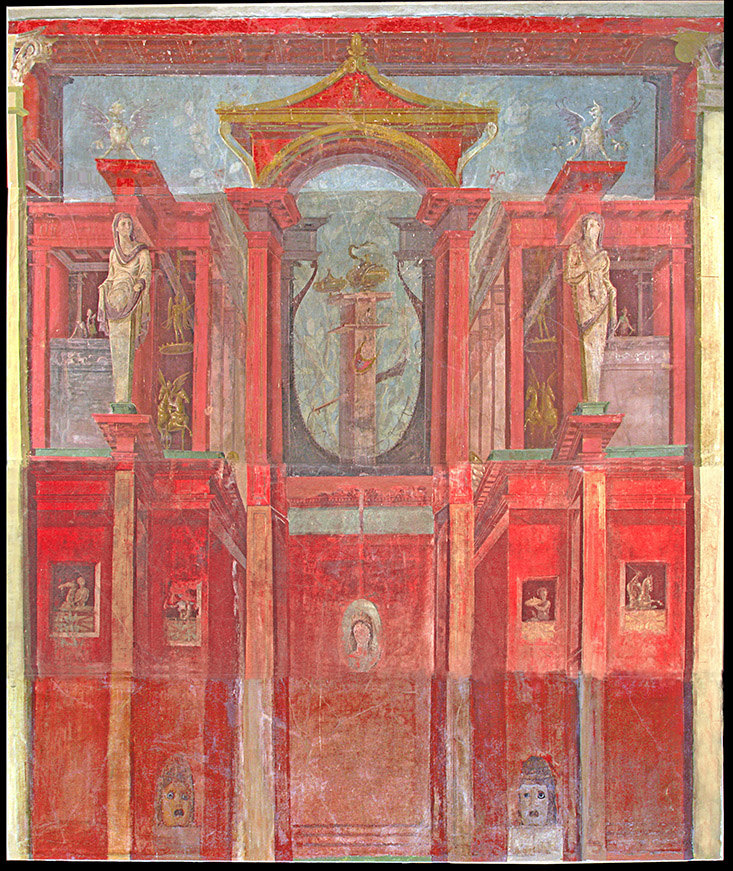

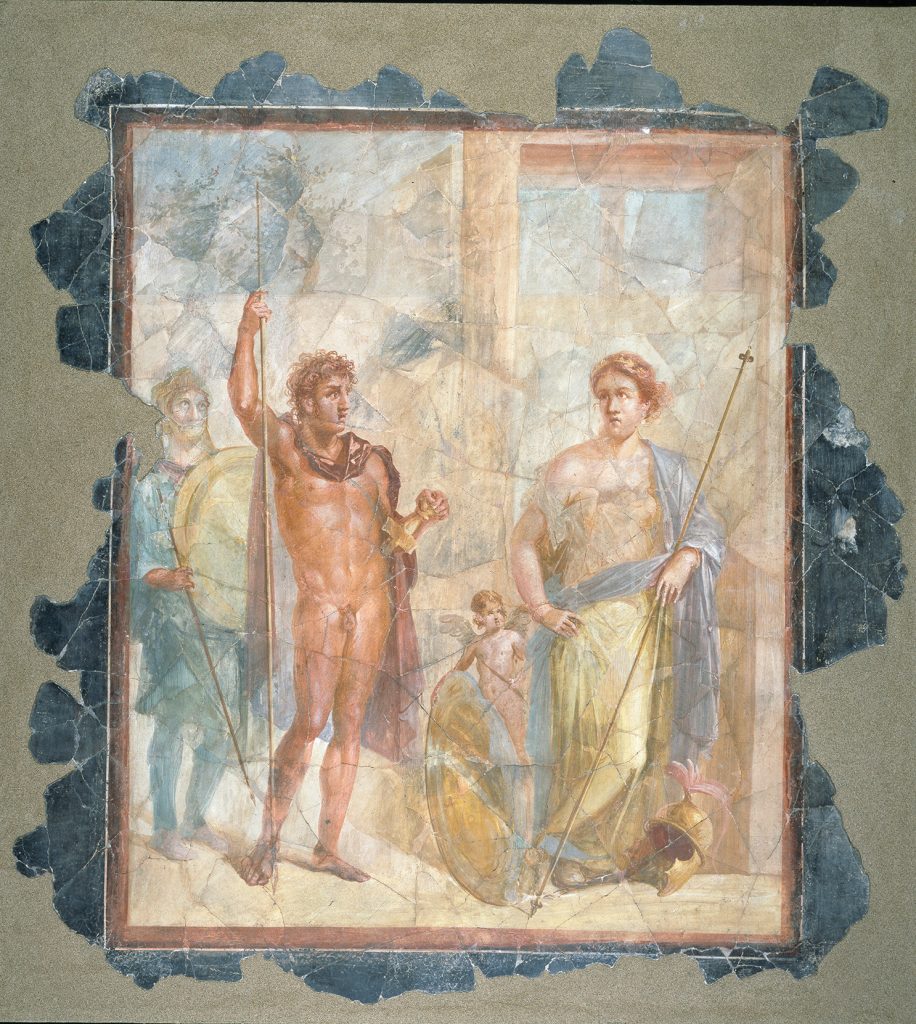

On the 25th January 2021, the Antiquarium was inaugurated with a new layout, and has become a museum venue dedicated to the permanent exhibition of finds that show and narrate the story of Pompeii. It has been completely refurbished, taking inspiration from what was the museum concept of Amedeo Maiuri, and by means of the most significant finds, traces the history of Pompeii from the Samnite era (4th century BC) until the tragic eruption of AD 79.

In addition to the most famous artefacts from the immense heritage of Pompeii, such as the frescoes of the House of the Golden Bracelet, the Moregine Silver Treasure and the triclinium of the House of Menander, finds unearthed by the most recent excavations undertaken by the Archaeological Park are also displayed, including fragments of First Style stucco from the fauces of the House of Orion, the amulet treasure from the House with the Garden and the recently produced casts of the victims from the Civita Giuliana villa.

The visit to the Antiquarium is also accompanied by two forms of digital media: a web-bot – a digital assistant able to provide simple and clear service information, and an audio narration which accompanies the visitor from the exhibition route to the discovery of several points of interest within the Archaeological Park of Pompeii.

Official in charge: Dr. Silvia Martina Bertesago